Our visit to Luang Prabang brought forth complex emotions.

These unanswered questions provided the opportunity to seek what Lincoln referred to as “the better angels of our nature.”

As seen from the window seat, Northern Thailand’s flat dry landscape gave way to lush, velvety mountains cloaked in deep gem-like shades of malachite and emerald. The plane flew us low, and we tried to forget that a friend had researched safety records of regional airlines serving our route to Luang Prabang.

It seemed as though a crash would be swallowed by the jungle, any wreckage hidden by its impenetrable canopy, and we, as its passengers, forgotten in an unsolved mystery. This was unsettling.

“Well, you see, Willard, in this war, things get confused out there. Power, ideals, the old morality, and practical military necessity. But out there with these natives, it must be a temptation to be God. Because there’s a conflict in every human heart, between the rational and irrational, between good and evil. And good does not always triumph. Sometimes, the dark side overcomes what Lincoln called the better angels of our nature.” – General Corman, Apocalypse Now

These were the hills into which Tai-speaking tribes migrated from China’s Guangxi sometime in the 8 – 10th centuries. Believing in a re-creation myth arising out of a great flood, they assigned their origin to three chiefs who had been spared. These three had been placed by the Great Deity to till the land near what is now Dien Bien Thu, just over today’s border in northern Vietnam.

The progeny of this divine restoration were both dark-skinned and light. Those with lighter skin were ruled by Khun Borom, whom the Lao consider to be the father of their race, in what was to become The Kingdom of One Million Elephants.

After we landed in Luang Prabang, our driver took us into town by what seemed like a back way. But actually, retracing it on the map later, we realized this was most direct. Muddy Phetsarat Road had more pedestrian traffic than any other kind in the early evening. We shared the lane with barefoot young men, raggedy children, a few bicyclists, and the occasional pushcart.

Narrowing further, Phetsarat approached the Nam Khan River, an even muddier stream with steep banks in this drier part of the year. Suddenly, the road became a precarious one-lane wooden bridge with two simple tracks made of flat boards. We could see through wide gaps in its trestles to the mire far below as our vehicle slowly traversed, and were relieved to hit solid pavement on the other side.

The Nam Khan makes a couple of S-bends before it empties into the Mekong here. In ancient days, pre-Laotian rulers had viewed this as the perfect location for a royal capital, strategically situated as it was on the Silk Route. Legend has it that Buddha rested here with a smile, as well as made the prediction that this spot would someday boast a city for the rich and powerful.

Legend also has it that this confluence is the home of the Phaya Naga, a supernatural, sacred marine creature similar to a dragon or serpent, which is prominent in Buddhist mythology and iconography. The naga’s evil predilections can be neutralized, or even channeled into protective generosity by ritual prayer ceremonies.

Founded by a warlord, and then kept as an administrative seat through various dynasties and principalities, by 1707, Luang Prabang was the capital of a kingdom by the same name. Annexed by Burma a few decades later, relations were friendly with the neighboring Kingdom of Champa which had been made a vassal by the Kingdom of Siam.

After Luang Prabang was ransacked by the Chinese Black Flag Army, France came to its rescue and enfolded it with two other kingdoms into the French protectorate of Laos in 1893. As such, Laos acted as a buffer – a role it would play throughout the 20th century to come – between British Thailand and other more valuable French protectorates in central and northern Vietnam.

Luang Prabang was occupied by the Japanese, Vichy France, Thai, Free French, and Chinese Nationalist forces during and after World War II. Beginning in 1946, when the French attempted to retake Vientiane and Luang Prabang, and through the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, when a secret American air base was located in Luang Prabang, the city was the center of air and ground warfare.

Truth is an illusion. It is only something we create from memories and wishes and fragments of dreams. The truth is what we want to believe. And sometimes lies are so essential they become part of the truth. – Elaine Russell, Across the Mekong River

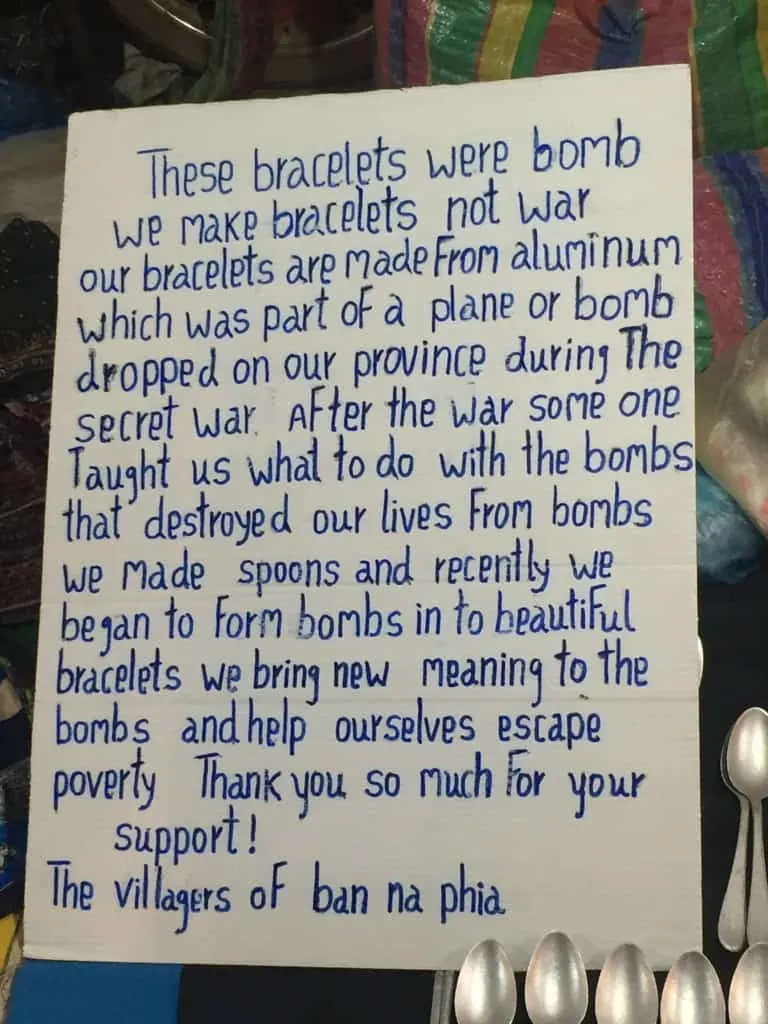

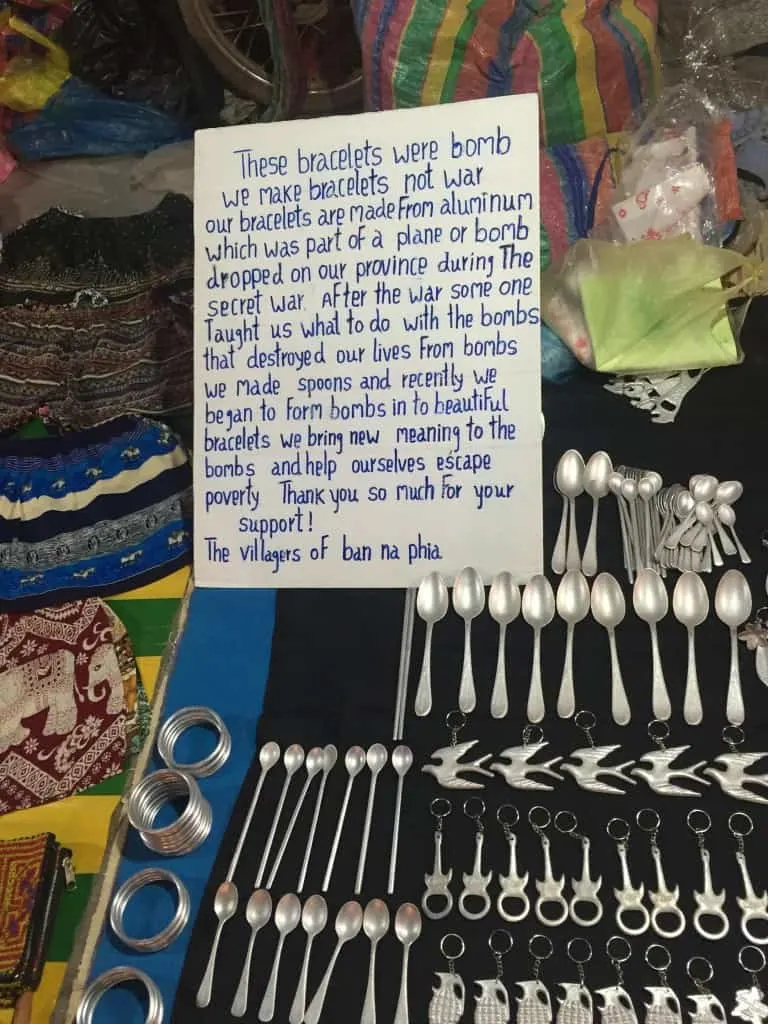

The Secret War, as it is known by Hmong and US Central Intelligence Agency Special Activities Division veterans, was a proxy war waged here between Cold War superpowers. During the Vietnam War, covert operatives and direct elements from the North Vietnamese Army (NVA), United States, Thailand and South Vietnam vied to control the Ho Chi Minh Trail supply route in the Laotian panhandle.

This was a seasonal war farther north in the area of Luang Prabang, suspended during the wet months of May through December. As the weather improved, NVA and communist sympathizers would emerge from Vietnam and within Laos to reinstate the flow of troops and supplies.

Beginning in 1961, the CIA recruited and trained Lao hill people from the Hmong, Yao, Dao and Shan tribes, supporting their guerrilla activities in northern Laos with air operations. The strategy was comprised of three parts: 1) disrupt and destroy the supply chain – much of which originated in China, 2) suppress the Pathet Lao communist group which threatened the Royal Lao government, and 3) protect the Laotian capitals (Luang Prabang and Vientiane).

Details about the Secret War in the United States remained sketchy during that time, and to this day, it is still little known. The governments of the United States and the Democratic Republic of [South] Vietnam officially denied its existence on a technicality: Laos had been declared neutral during the Geneva Conference of 1954. These denials belied the fact that Laos was subjected to the heaviest bombing campaign ever waged on a country in any conflict.

“Well, we had all those planes sitting around and couldn’t just let them stay there with nothing to do.” – U. S. Deputy Chief of Mission Monteagle Stearns, testimony to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Ninety-First Congress, October, 1969.

It is only lately that statistical evidence and conclusions have emerged. Martin Stuart-Fox, a Queensland University historian quoted in USA Today maintains that “. . . on a per capita basis, Laos remains the most heavily bombed nation in the history of warfare.”

“Much of my life over the past 40 plus years has been spent trying to understand the deeper reasons why the richest of the species would bomb the poorest this way, what it really tells us about humanity in general and America in particular.” – Fred Branfman, author of Voices From the Plain of Jars, writing in Alternet.

More than thirty years thereafter, USA Today reported, “From 1964 through 1973, the United States flew 580,000 bombing runs over Laos — one every 9 minutes for 10 years. More than 2 million tons of ordnance was unloaded on the countryside, double the amount dropped on Nazi Germany in World War II.” Cluster bombs were the weapon of choice, designed to penetrate the canopied forests we’d flown over some 50 years hence.

“The thoughts of worldly men are for ever regulated by a moral law of gravitation, which, like the physical one, holds them down to earth. . .They are like some wise men, who, learning to know each planet by its Latin name, have quite forgotten such small heavenly constellations as Charity, Forbearance, Universal Love, and Mercy, although they shine by night and day so brightly that the blind may see them; and who, looking upward at the spangled sky, see nothing there but the reflection of their own great wisdom and book-learning. . .It is curious to imagine these people of the world, busy in thought, turning their eyes towards the countless spheres that shine above us, and making them reflect the only images their minds contain. . . So do the shadows of our own desires stand between us and our better angels, and thus their brightness is eclipsed.” – Charles Dickens, Barnaby Rudge, Chapter 29

In 1975, Pathet Lao communists eliminated the Luang Prabang monarchy with help from North Vietnam and established government control. This birthed what is now known as the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, a socialist state run by the Communist Party. In May of that year, the government newspaper declared the Hmong people would be exterminated completely for their role in the Secret War.

A clandestine American operation ensued to airlift the most at-risk Hmong leaders and their families to Thailand, but lasted for only two days. By the end of the year, over 40,000 Hmong had taken refuge in Thailand, escaping on foot or via the Mekong River. Others fled deep into the mountain forests, threatened by starvation and hunted by the Lao army.

Over the next seven years almost 60,000 Laotian hill tribespeople were resettled in the United States. The Pathet Lao is accused of genocide, estimated to have killed up to 100,000 Hmong (25% of their total population), although the government characterizes this as lawful in the face of their “rebellion.” In 2008, the Thai government began repatriating Lao refugees by forced deportation, even in the face of Lao military atrocities against them.

“They had names, these people: Thao, Bounphet, Khamphong, Loung. They had treasured wives and husbands, children and grandparents, buffaloes and homes, rice fields and temples. And they had dreams — and as much right to these dreams as did any of the U.S. leaders who obliterated them.” – Fred Branfman, writing in Salon, May 2001.

Today, Luang Prabang, with about 50,000 residents, is a UNESCO heritage site, known for its Buddhist temples and monasteries. UNESCO cites the town center as “an outstanding example of the fusion of traditional architecture and Lao urban structures with those built by the European colonial authorities in the 19th and 20th centuries.” It is home to both royal residences and religious structures.

The various religious Wats (or pagodas) have intricate carved and painted decorations.

Throughout Laos, it is customary for boys and young men to spend variable amounts of time with the monks, preparing for marriage, being educated, learning temple restoration techniques, or taking lifelong vocation. Monks interpret dreams, practice traditional medicines and provide religious and practical counsel.

Mystical ceremonies designed to pay tribute to the mythical naga and ward off evil spirits, along with processionals and morning alms rotations, create a sanctified atmosphere in Luang Prabang which is harmonious with the natural environment. Animistic and shamanistic beliefs overlap with the traditional Buddhist practice to acknowledge territorial spirits who hold dominion over houses, villages, cities, and the realm.

Spirits are often ceremonially called to preside over special occasions such as weddings and birthdays. Their symbols and legends adorn the temples and other buildings.

We found the energy in today’s Luang Prabang complex, reflecting its volatile and sorrowful history as well as its reputation as an off-the-path, relatively inexpensive Southeast Asia destination. It had a full complement of visitors to match every aspect.

A boozy backpacker scene was rife with instances of public inebriation, all-nighters at the Utopia bowling alley, and rope-swinging at the waterfalls outside of town. There were travelers lamenting the presence and higher prices of pseudo-gentrification in the wake of increased tourism and UNESCO certification. This, not surprisingly, tended to occur while they were partaking of same: the wine bars, pizza places, souvenir handicrafts at the night market, and whichever other “too-touristy” elements specifically stuck in their craw.

Others were seemingly bent on what the Seattle Times calls a “WHS [World Heritage Site] quest,” presumably notching up quantitative proof that they fell solidly under the more prestigious and desirable “traveler” umbrella, as opposed to the mere tourist side of things.

We’d come with few expectations and far less background knowledge than we’ve shared with you in this post. Outside of boating the Mekong River, we left things in Luang Prabang unscripted. This gave us time to “be” and observe.

The upshot is that we were troubled, and after researching for necessary context perhaps even more so.

Why were so many of the locals meek and fearfully subservient, much more so than the typically eager-to-please southeast Asian service standard?

Why were the Pak Ou caves of standing Buddhas, supposedly a highly sacred site, beyond filthy? Why was this site neglected with many of the statues damaged despite the myriad and rather demanding requests for offerings and donations from hundreds of daily visitors?

Where were all the customers at the night market going to come from to buy all this obviously mass-produced merchandise? How much does a vendor make compared with the one-third of the population of Laos who live on less than $1.25USD per day?

Who really participated in the supply chain at the seemingly deserted handicraft village we visited along the Mekong?

What had happened to the former residents of Luang Prabang forced out by rising prices and land values after the UNESCO designation?

We could go on and on, of course, but perhaps the most heartbreaking question of all is, why did the United States spend almost $12 million (in 2015 dollars) per day over ten years dropping bombs on Laos, yet provide the equivalent of only 8 of those days’ expenditure ($85 million) in Unexploded Ordnance assistance?

Our brief stay ended with these and other unanswered questions. This has been a difficult post to write for so many reasons, but the questions don’t go away just because you don’t write about them. Would we return to Laos and Luang Prabang? Most definitely.

“We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory will swell when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.” – Abraham Lincoln

Travel isn’t just about the prettier faces or the better time. While it’s fun to splash in waterfalls and buy inexpensive souvenirs and drinks, it’s about the more difficult moments, too.

Luang Prabang delivered us a chance to understand how shared history has vastly different impacts. It provided an opportunity for deeper empathy. It induced us to re-examine long-held conceptions about global roles and responsibilities. Perhaps most importantly, Luang Prabang gave us a moment from which to reach toward atonement and our better angels, as precariously distant as they may be.

More Information About Luang Prabang, Laos

If You Go:

We recommend the Lakhangthong Boutique Hotel, a traditional Lao guesthouse with certain modern amenities: air conditioning and deep soaking tub, free wi-fi, and complimentary bicycles with which to explore town. This guesthouse is located away from the riverfront in a more local neighborhood, close to Wat Monorom, yet only a ten minute walk to the Night Market and waterfront restaurants.

The hotel will arrange for your van transfer to and from the airport, as well as any local attractions via tuk-tuk. Staff is eager to please, but limited in their options: for example, there was no printer on site, so no pre-printing boarding documents, visa letter, etc. for our next stop. Check out is a leisurely 1:30pm and breakfast is included in your room rate. The Lakhangthong Boutique Hotel is a non-smoking hotel.

Pinnable Image:

Tips for Trip Success

Book Your Flight

Find an inexpensive flight by using Kayak, a favorite of ours because it regularly returns less expensive flight options from a variety of airlines.

Book Your Hotel or Special Accommodation

We are big fans of Booking.com. We like their review system and photos. If we want to see more reviews and additional booking options, we go to Expedia.

You Need Travel Insurance!

Good travel insurance means having total peace of mind. Travel insurance protects you when your medical insurance often will not and better than what you get from your credit card. It will provide comprehensive coverage should you need medical treatment or return to the United States, compensation for trip interruption, baggage loss, and other situations.Find the Perfect Insurance Plan for Your Trip

PassingThru is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

To view PassingThru’s privacy policy, click here.

Mike Hinshaw

Saturday 23rd of February 2019

Fascinating read young lady. I have found similar quandaries on a few trips myself. The atrocities human beings level against each other are enormous and in most cases unexplainable. It's also worth mentioning how societies can bounce back and move ahead after these events have transpired. I think the desire to survive always kicks in and people focus more on the future in order to shed their ill feelings of the past. Something in our DNA pushes this innate yearning for life. As long as this remains we will be okay, I firmly believe. Thanks for reminding us to pause an reflect!

Jackie Smith

Thursday 23rd of June 2016

An excellent post, Betsy and I agree that travel isn't always about the 'happy' stuff (I seldom read posts about 'sponsored stays or goods' any longer) -- I prefer the 'real world' experiences -- even when tough to write or read. Another great (but sad) read. We have welcomed many Hmong into the Pacific Northwest where quite a few are raising flower gardens and selling handiwork at Farmer's Markets and tourist venues and others have gone on to open restaurants. Many of their children have gone through the school system and have begun successful careers, I am happy to report.

Betsy Wuebker

Friday 24th of June 2016

Hi Jackie - Yes, it seems assimilation is more successful in the second generation in this case. Thanks.

Rajkumar

Tuesday 24th of May 2016

Hello Betsy, Luang Prabang is really incredible and peaceful place I have ever seen. Thanks for sharing such deep history of Luang Prabang. It truly deserves in the UNESCO world heritage lists.

Betsy Wuebker

Tuesday 24th of May 2016

Hi Rajkumar - Thank you so much. Glad you enjoyed it!

Kevin Wagar

Tuesday 15th of March 2016

Wonderful walk through both modern and historical Laos. We have been considering visiting here next year with our children and we will keep this post saved so we can reference it!

Betsy Wuebker

Friday 18th of March 2016

Hi Kevin - Luang Prabang would be very interesting for kids. Diving into the complicated history can be for us adults.

Lisa Martin

Tuesday 15th of March 2016

It is almost hard to believe that such a beautiful part of the world has faced so much tragedy. Thank you for sharing this post, perhaps it will shine a light on what has gone one here to others who may have just joined the tourist track. It must have been troubling to learn about the history while you were staying there.

Betsy Wuebker

Friday 18th of March 2016

Hi Lisa - It was more troubling after we left as I began to more thoroughly research. While we were there, the energy was heavy and sad, but not knowing the details made it difficult to understand why at the time.