When an unexpected medical emergency in Colombia occurred, we had to scramble. Without medical insurance for travel abroad, I’d be dead now.

No one wants a medical emergency abroad, but you can and should prepare for a travel-insurance assisted health scare overseas. Read the story of our medical emergency in South America and understand why choosing the best medical insurance for travel abroad is imperative.

Beautiful Cartagena – we fell in love with this wonderful seaside city on Colombia’s Caribbean coast

This post may contain affiliate links and/or references to our advertisers. We may receive compensation when you click on or make a purchase using these links.

How Our Medical Emergency in Colombia Started and Played Out

Our medical emergency in Colombia began as all nightmares do: innocently enough. We’d been housesitting in Boquete, Panama, for about six months and needed to make a visa run. Thirty days out, and we could return again for another sit at the same beautiful location in the lovely home of a fabulous couple. So, we booked a series of resort and guesthouse stays in Colombia, right next door. It was going to be a fabulous vacation in a new country on a new continent!

Our favorite part of daily life in Cartagena was the sweet little plazuela in our neighborhood

Our first ten days in Cartagena were glorious. In Cartagena’s picturesque Getsemaní neighborhood, we imagined ourselves residents for an even longer term in the future. We loved the combination of Caribbean and Old World Spanish elements, the lifestyle in the plazas and on the sidewalks, the fruit vendors who awakened us with their sing-song calls, and the morning coffee men with whom Pete practiced his Spanish in the wee hours. Our landlady was a dear, our balcony room was simple and charming, and prices were cheap.

Our street in Cartagena

Next up was an oceanside resort northeast of Santa Marta, close by the famous Tayrona National Park. Checking in, we were thrilled that our third floor suite looked over the sea. I love falling asleep to crashing waves!

View of the pool from our third floor suite with the Caribbean just beyond the mangroves to the right

Our suite was also just mere steps from the pool and the restaurant, where we needed to access the wifi to keep up with our work schedule. Quickly, we settled in to a daily routine, setting up at the breakfast table, working through lunch, and then a refreshing swim and siesta before dinner and an early bed time.

The resort pool where the nightmare began in an instant

People always talk about how things can change in an instant, so much so that it’s a cliché. But here’s the thing: clichés are rooted in truth. That’s how they get that way. And the truth is, in an instant, our Colombian idyll was over, and we were thrust into a medical emergency in South America. One minute, we’re at the swim-up bar, refreshing umbrella drinks in hand, and the next, I couldn’t get out of the pool.

– – –

I can’t get out of the pool because I can’t breathe. I’m flailing around on the shallow reverse infinity edge of the pool like a beached whale, thinking to myself, “Let’s not make a scene here.” Watching Pete, who’d gone on ahead oblivious to my difficulties, disappear down the steps toward our building, somehow, I get on all fours and then will myself to stand, teetering. Cannot breathe. Oh my God. Don’t fall.

Is anyone looking? Oh, good, they’re not. Nobody ever notices women of a certain age anyway, anywhere, anymore. We’re invisible: sales clerks skip right over us to the next person in line, we can sit waiting for a drink or a menu forever, and it doesn’t really matter what we wear because nobody is paying attention. For once, I’m grateful for this.

Slowly, I set forth, wrapped in my towel. I cannot get any oxygen. I decide to take deeper, slower breaths and hold them longer. Carefully, I step. This foot, then that. Somehow I make my way out of the pool area. Christ, why do we have to be on the third floor with no elevator? This means there are six flights of eight steps apiece. Thank God there is a landing between each flight, where I can stop, seemingly casual, gaze at the water, try not to die.

The door is open and I stagger in. “Can. Not. Catch. My. Breath.” in answer to Pete’s questioning look. I sink into a patio chair and put my head between my knees, hyperventilating. Eventually, after about fifteen long minutes, I calm. We dress and go down for dinner. I’m okay if I go slowly, but I’m exhausted by the time we get to the dining room. What the fuck? I can’t fucking breathe! I stave off panic, finish a small meal, and struggle back to the room.

The next morning things are no better. Pete decides we’re going to check out and head back into Santa Marta. He thinks I’m having a cardiac event, goes to the resort store for baby aspirin and summons the resort nurse. She takes my blood pressure, which is in the 180s. With my high school Spanish, I ascertain she wants to give me a pill for this, and I take it.

We pack up. It’s a 30 minute drive into Santa Marta by taxi; he’ll pick us up at the resort office. My heart sinks when I see how far the office is to walk. The reality is that it’s about 50 yards. I have to stop every ten steps. I feel relieved when the taxi arrives.

Fortunately, we have purchased short term medical insurance for travel abroad, and Pete has located a cardiac care clinic in Santa Marta. We hit the road. I lean against the door in the back seat and try to catch my breath.

Tip: Overseas health insurance can be a complicated matter. Educate yourself. Many US health insurance companies, and Medicare, will not cover you out of the country. Even if your domestic insurance carrier will reimburse expenses, they can add up quickly in an emergency. We always purchase medical insurance for travel abroad from a travel insurance company. While you think you might be covered via your credit card, think again and be sure.

The highway from Tayrona back to Santa Marta is two lanes of bumpy black top which links mountain villages and clusters of local businesses. Suddenly, I have to pee. The blood pressure med the resort nurse gave me must have been a water pill. Every jolt is agonizing.

The driver says, “Sí, señora, allá” when I query, as we slow toward a police checkpoint. There is a public restroom. I’ll spare you further description. Suffice to say I barely make it, but make it I do and we press on with me leaning back into the taxi seat, gasping for air.

Vastly relieved, I’m happy to see Santa Marta proper emerge into view. The cardiac clinic is a low slung cluster of attractive hacienda style buildings with a security guard shack and a chain across the entrance. The guard waves us back. “Por qué?” we ask. “Por qué la clinica está cerrado.” The clinic is closed. “Problemas económicas.” For good.

We don’t have a Plan B. I can’t breathe.

Quickly, Pete locates another clinic using Google maps. It’s a few short blocks away and the taxi drops us off at the Emergency entrance. “Buen suerte, Señora. Vaya con Diós,” our driver intones. It’s clear he’s not optimistic about my fate.

This clinic is chaotic. After a few administrative tasks, the major of which is a deposit of $1 million pesos (about $300USD), I am admitted into the Emergency Department and we are put into a curtained space.

Things happen pretty fast after this: a portable EKG machine registers no apparent abnormalities, BP is moderately high and rising. I get more meds.

The cardiologist, who is a dead ringer for actress Lucy Liu, wants me in for an echocardiogram. I am wheeled through a maze of hallways that have all sorts of random people just hanging around. Everyone appears to be surprised there is a gringa of a certain age in a vivid green skirt rolling past.

The imaging and equipment look like what was used on me for ultrasound when I was pregnant with the kids. Thirty years ago. It’s got that almond yellow discoloration white plastic gets when it’s old.

Lucy presses hard with the tool through the gel on my chest, going up and down my esophagus, stopping and looking, looking again. She dictates to an assistant in Spanish, finishes me up and I get wheeled back through the all the people in the hall to the ER, where Pete is waiting.

Lucy and the ER doc, whom I’ve dubbed Dr. Guapo because he’s so handsome, come into my curtained off space for a chat in Spanish. “You have a problem with your aorta,” she says, slowly so that I can understand and tell Pete. “I have three hypotheses: 1) hypertension, 2) aorta dissection or 3) embolism.”

She says I need cuidado intensivo: Intensive Care. When do I need this, I ask. Right now, they say. I turn to Pete, “Well, shit.” The docs laugh, nervously. This is English they recognize.

In the wheelchair again I go, and Pete stashes our luggage behind Guapo’s desk. There is no time to worry if it will be secure. My purse is on my lap. At the ICU entrance we are stopped. I am not allowed my purse, not even my cellphone, and Pete can’t come in. Visiting hour is over.

I have to go in with the clothes on my back and that’s it.

After a bit of an argument, I surrender. I don’t have the energy because I still can’t breathe, goddammit. The doors open and my eyes well up. I am now officially scared. “This is what it feels like to completely lose your self-agency,” I think, helplessly.

The doors close behind us, leaving Pete on the outside until morning. He has nowhere to go. Tears are streaming down my face and I’m glad he can’t see me.

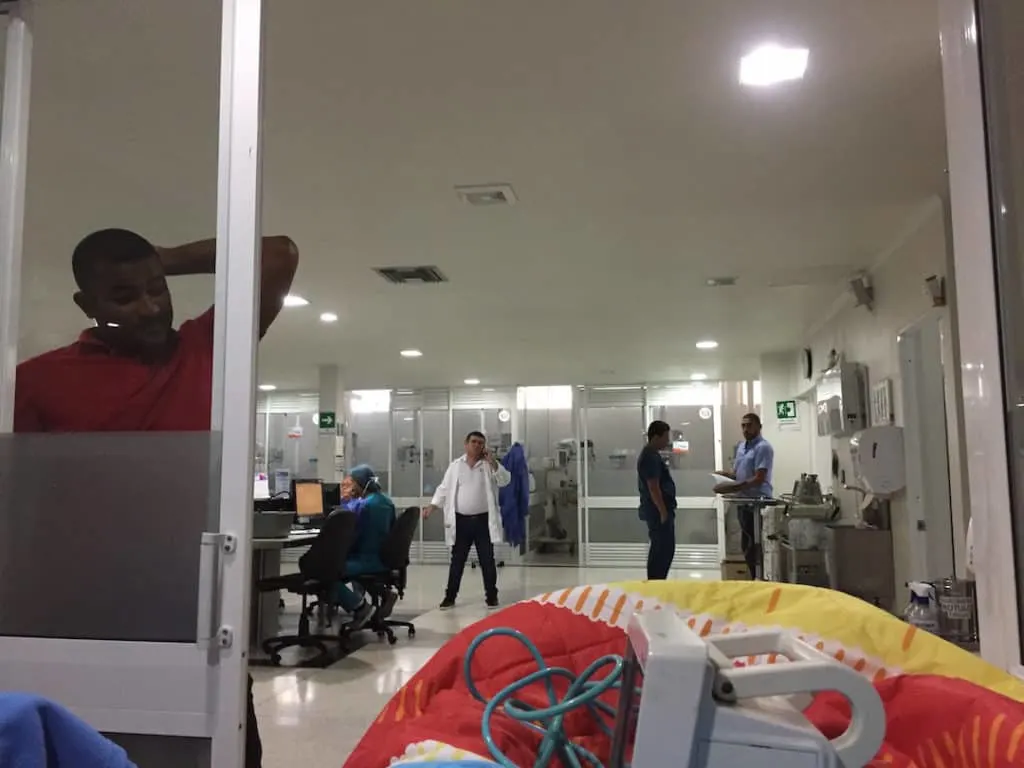

I’m wheeled through the unit to a space in the back corner. All the walls only go halfway up, the rest is glass to the ceiling. It looks like there are about 8 other patient spaces. In mine, there is an open little anteroom in which, inexplicably, a stainless steel toilet is bolted to the wall.

My bed is in the room adjacent, through two glass swinging doors. We stop and they indicate I must get into the bed, but horrifyingly, I can’t. The bed linen is filthy with bloodstains and other fluid spills.

I object, my terror transformed into outrage: “No es limpia.” Yes, it’s clean, they counter. What are they, trying to gaslight me? It’s the most disgusting prospect to date!

Belatedly, I realize, the “sheets” are polyester fabric, most likely selected to be more comfortable in the tropical heat (or maybe less expensive, too). There is no chance that they can ever be sufficiently laundered to remove these stains.

Gingerly, I situate myself, still in my resort clothes. They puncture the back of my hand and get an IV going. Of what? No one says. I’m stickered up with wires and hooked up to monitor. If I don’t move, I can breathe. So there’s that and I don’t.

There is loud, raucous laughter coming from the nurse’s desk and party music is playing. Clearly, patients get their rest in spite of everything in here. It’s going to be a long night, I tell myself.

And it is a very long night. There are painful blood draws every couple of hours – why can no one ever find my veins? The overhead lights remain on in a torturous glare. I see staff members peering at me through the glass several times.

The charge nurse speaks to me loudly, patronizing me as if I’m an imbecile. I realize I need to be on his good side, but I want to slap the smarmy expression right off his face. There is no escape.

In the morning, my breakfast is delivered: two dry cornmeal wafers stuffed with grains of dry local white cheese in a styrofoam Big Mac box. These are beyond inedible, but I try to take a few bites. I get to wash them down with water, also in a styrofoam cup. No time for concern if it’s tap water or not. It’s this or go without. I drink.

I know nothing of what is going to happen to me. I push the call button attached to my bed in vain. Later, I find out it has been disconnected. They all are.

I flag down a nurse on rounds and explain I need to pee. She wants me to use a bed pan and I refuse. I honestly don’t think I can get enough oxygen to contort myself on to it. Finally, I convince her to take me to the bathroom in the wheelchair.

We travel a maze of back hallways and come upon the room where all the bedpans go, which has a toilet with no seat. Thankfully, I know how to hover successfully from time spent in Asia.

But, I make the mistake of looking around the room as I go, my skirt pulled high above the grunge on the floor. There are ancient piles of dirt and enormous dust bunnies behind the door.

I look to my right to see the men’s portable urinals carelessly stacked, each with varying amounts of liquid still in them. I deliberately avoid looking at the bedpans. At least I can’t breathe in whatever toxic bacteria might be in the air in here, I think, because I can’t breathe! I laugh to myself, on the verge of hysteria.

Back in the room, Pete arrives at 11am with bottled water, and my cellphone; we wait in vain for someone to clue us in during the hour he’s allowed. He can’t stay any longer, they explain, because of infectious diseases around. Like what? Well, like tuberculosis and worse. Surely tuberculosis understands it cannot infect visitors between the hours of 11-12 and 5-6 pm, then? Nothing is making sense.

Finally at 2pm, Lucy Liu arrives. (Later I learn she’s a contracted specialist, not on staff. As such, she comes in after 2pm most days.)

Poor Lucy. I unload on her, tearfully, angrily. Why has no doctor been to see me, or even talked to me about what is going to happen for almost 24 hours? My non-functioning call button, no food until “breakfast” this morning, the partying at the nurse’s station making it impossible to sleep. Her eyes widen and she promises to find out.

Lucy comes back with the news that I’m to get an angiogram in short order. Excitedly, I text Pete with this info. But wait, she says, didn’t you say you’ve eaten today? Well, yes, I had two small bites of the inedible wafer. Because of this the angiogram will have to be postponed until tomorrow. If I’m not supposed to eat, why did no one tell me and why did they deliver food? She has no answer and says I must not have anything after 8pm.

I text Pete again and ask him to bring food. By the time he arrives at 5 with a Subway sandwich, I am ravenous. I’m still in my street clothes, having slept in them. Could we at least get a hospital gown, we ask? One is brought in and tied around the wires and IV line.

I’m shivering with cold in the blasting air conditioning, are there no blankets? There are not. The nurse brings several more stained polyester sheets and folds them into a makeshift pillow and covers.

Pete’s face is beet red with frustration. While I’ve been laying there, he’s been dealing with administration, depositing more funds – every time it’s 1 million pesos more, attempting to liaison with our insurance company, finding a place to stay and worrying.

Now an entire day has passed and nothing has happened. One of the administrative staff who speaks a little English suggests Pete get a blood pressure check. He looks too red. No, really?

I still can’t breathe, but I’m pissed. I take my computer from Pete’s backpack, fire up Google Voice and harangue our Allianz Insurance adjuster in the US. I can hear the shock in the poor guy’s voice when I tell him who and where I am. They promise to take over with the clinic administration, and I’m thankful. I disconnect, exhausted.

We can’t totally be sure because of the language barrier, but we’re still not getting any answers. “I think you’re going to have to go Turkish on them,” I say to Pete. This is the verbal shorthand we have for the loud insistence we’ve found necessary to employ in certain locations when there is a cultural difference requiring “encouragement.” This is not our nature but if you don’t insist in certain places, you often don’t get.

Loved ones waiting outside the clinic door as seen from the ambulance gurney

Either the Turkish method has worked or Lucy has pulled rank: all of a sudden there’s a guy in a plaid shirt with an interpreter, assuring me they will do their best. Who is he? I wonder. Oh, he’s the boss of all the doctors, the nurse tells me. “En el nombre de Jesu Cristo,” she intones before sticking me for another blood draw. They’re running out of veins they can use.

The next morning it’s angiogram day and no delicious meals arrive to tempt me. I am to be transported by ambulance to the offsite location where the procedure will be performed. I’m wheeled past the groups of unhappy people in the hallways and the street people loitering by the clinic door. My gurney is loaded into the ambulance and Pete hops in the front seat.

The ambulance driver – Danny DeVito’s doppelgänger – starts up and we go. . .all of 12 feet. I am unloaded again in front of the same astonished people. Evidently, protocol demands an ambulance trip right next door. The hilarity of this causes near hysteria in both of us. Even Danny laughs, shrugging. Que podemos hacer? (What can we do?)

We travel to an upper floor and Danny negotiates my gurney into a series of tight turns. We wind up in a small reception office where several staff members are eating their bag lunches. This is where Pete has to stay while I have the procedure. Through another door, and I’ve arrived in a room with bookcases, another desk piled high with papers, and the bench and equipment where the procedure will take place.

The wire is threaded up through my right wrist and into my heart. I am in twilight state, similar to what you might have during a colonoscopy. It seems like no time passes and the doctor announces, “El corozón es normál.” On the strength of this good news, I am wheeled out. Danny transports me back the twelve feet in the ambulance to the clinic building and I’m taken into the ICU again. I still can’t breathe.

The next day, Pete talks to Lucy about the angiogram. It’s unclear whether there’s now a plan. It seems as though they might have thought the angiogram would confirm her first hypothesis and they could then insert a stent and fix me. The “normál” result appears to have countermanded these assumptions. He is not let in to see me in the morning out of deference to a grieving family visiting their recently deceased relative.

He comes back again at 5pm and neither one of us has any answers. In the interim, I’ve been left on the bedpan in my own waste for close to an hour during nurses’ shift change and rounds. You haven’t lived until you’re vainly signaling half a dozen people looking through the window up your hoo-hah to come and help you and no one responds.

Later, I’m given a bed bath using freezing cold water poured from a bucket into my body crevices. (Many showers, bathtubs and faucets in this part of the world do not have hot water taps.)

I am grateful for the comforter and pillow Pete purchased and brought in after these two incidents. Later we learn that in many public clinics it is customary for patients’ families to bring bedding and food in for their loved one. No one sees fit to let us know.

To top it off, my IV drip machine is malfunctioning. It signals for an hour, chirping steadily and loudly. No one comes to look for what’s wrong. This electronic water torture continues for an hour. Someone who must’ve drawn the short straw finally comes in to change it out and I let her have it.

What a sight I must be: a fat old, greasy haired Americana berating her in broken Spanish. I hate myself for becoming so agitated and irrational. Many of these people are doing the best they can with what they have, and they don’t have much. Others are not doing their best. Pete says I’m being too nice in my assessment.

My oxygen absorption rate is now averaging in the mid to high 80s. I feel like this is affecting my cognition as well as my behavior, so I ask for oxygen supplementation. I’m told they won’t give it until I drop to 80% or below. I am stunned by this response and afraid of permanent brain damage.

The shift changes and I overhear two of the nurses remark on the color of my eyes. Evidently, I am the main exhibit in this zoo. Everyone sees me when they come to empty bedpans in the toilet in my anteroom.

I am moved without explanation out of the back corner cubicle and into the one next to me, from which I have a better view of the entire floor. It’s another long night of partying at the nursing desk in between frantic ministrations to the poor soul two cubicles down on my left.

There is a pastor praying at the foot of the bed of the person in the center, and several nurses washing a woman who is either comatose or dead across the way from me. Her skin is a beautiful caramel color and they turn her this way and that. I think she’d be mortified at what we all can see of her, and then I remind myself I was in a much less dignified position myself shortly before.

It’s Saturday night and I’m closer to the nurses’ desk from which the music and laughter blares. My nightly blood draw is a failure. I am officially out of accessible arm veins. Two of the male nurses come in, wipe my butt and stick me in the groin for a successful draw. I’m not even embarrassed by this. Exhausted, I sleep.

“Mommy. . . Mommy. . .Mommy!” The faint cries from so far away waft through the fog. Which of the kids is lost, I wonder? Robin? Or Geoffrey? I need to wake up but I don’t want to, no, I can’t. What ever is wrong? I’m sleeping! Ever so slowly, I get my eyelids to respond.

“Oh, Mommy.” The sadness. Where am I? I’m a side sleeper, but I’m lying flat. What am I looking at? In a sea of white, gradually the details take shape: a misshapen recessed light, a cracked access panel of some sort. Christ, what a lousy paint job, I think, randomly. Just like everything else in this clinic, careless and dingy.

“Mámi…” The sobbing. I look to my left. Through the glass, a woman is leaning over the bed two cubicles down. “Oh, mámi, mámi, mámi,” she wails. Oh, I realize. It is morning and another person has died.

I’m trapped in a nightmare of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest proportions, and I don’t need a professional statistician to prove that eventually it’s going to be my number that comes up. What I need is tertiary care. Lucy, on a brief check-in, all but confirms my needs are way out of this clinic’s league.

Pete arrives and I’m listless. What happened to the woman two doors down, he wonders and I tell him. Glumly, we don’t have much to talk about. It’s Sunday, and after he leaves, things are quiet and I get more sleep. By the time he arrives again at 5, there has been another death and he has to wait to come in after the family is finished.

It’s 7pm by this time – another day has passed with no solutions. I can feel myself slipping further and further. I’m caring less and less about what’s going to happen to me and I know it’s not going to be long before I don’t care at all.

I tell Pete, “Tomorrow’s Monday. It seems to me we’ve got about 12 hours to get me out of here, or I’m a goner.” In the meantime, people on the outside – some we know and some we don’t – are planning and awaiting my escape.

– – –

If you’ve ever doubted that social media is a good thing, I can tell you with absolute certainty that I’d be dead without it. While I was languishing, oxygen-deprived, in the clinic in Santa Marta, a childhood friend of Pete’s reached out to a relative by marriage in Bogotá, who in turn had a relative who is a cardiologist in Barranquilla, a coastal city three hours by car from Santa Marta. If we could somehow get to her clinic, Clinica del Caribe, they could provide the level of care I needed.

In the meantime, another Colombian relative in Barranquilla phoned a school chum, who lived in Santa Marta. That person had married into the family of the provincial governor. Unbeknownst to us, the head administrator of the Santa Marta clinic received a telephone call late that night from the governor with a bit of “encouragement” regarding my case.

The young Colombian relatives in Barranquilla insisted Pete stay at their apartment when we arrived. When this was all conveyed to Pete, he cried.

The next morning, I was visited by a very obsequious administrator accompanied by a translator. They were going to do everything they possibly could to move me to Barranquilla. This would happen by ambulance as soon as possible that very morning. Thanking them, I inferred they couldn’t wait to be rid of me as much as I wanted to be rid of them. I texted Pete and he hurried over.

A very worried husband puts his game face on, happy we are finally leaving by ambulance

By 2 p.m., we realized we should have known better, and Pete went Turkish again on the administrative office. They weren’t going to let us go without receiving a final payment. No one seemed to know the amount, but it was either the equivalent of $300 or $600. Why were we kept waiting when we just could have paid it? Pete roared. All of a sudden, it was okay, we could go.

Within minutes, Danny DeVito and two companions, both named Jesus, suddenly appeared and loaded me on to a gurney.

One of the ICU nurses and me as I’m leaving. My wrist is still bandaged from the angiogram procedure.

Jesus and Jesus were crammed in back with me and our luggage.

Jesus #1 and others loading me in the ambulance.

Pete was in front again with Danny for the harrowing trip through chaotic traffic down the coast to Barranquilla.

Looking back, it’s another miracle that I actually survived the ambulance ride, but how could I not with Jesus times two with me? It was a long three hours. At one point, I must have drifted off because I awakened to Jesus #2 stroking my arm to keep me awake. It wouldn’t have been a good look to arrive comatose, I suppose.

Jesus #2 keeps an eye on my numbers in the back of the ambulance

Eventually, we pulled in to Clinica del Caribe at about 5 p.m. Clearly, they had been waiting and hustled me in to their ICU. Before I was even unloaded off the gurney, I received a cannula with blessed oxygen flowing into my system.

The view from my “casita” in Clinica del Caribe’s ICU. Jesus is going over my paperwork.

Upon introducing herself, my personal angel of mercy, Gladys, drew herself up to her entire height of about 4’11” and announced she was stripping me down to my birthday suit. Holding the dreadful Santa Marta hospital gown at arm’s length, she dropped it unceremoniously into the bin.

In a matter of minutes after arrival at Clinica del Caribe, I was in a cocoon of soft cotton bedclothes, warm blankets, and fluffy pillows. And best of all, I could breathe.

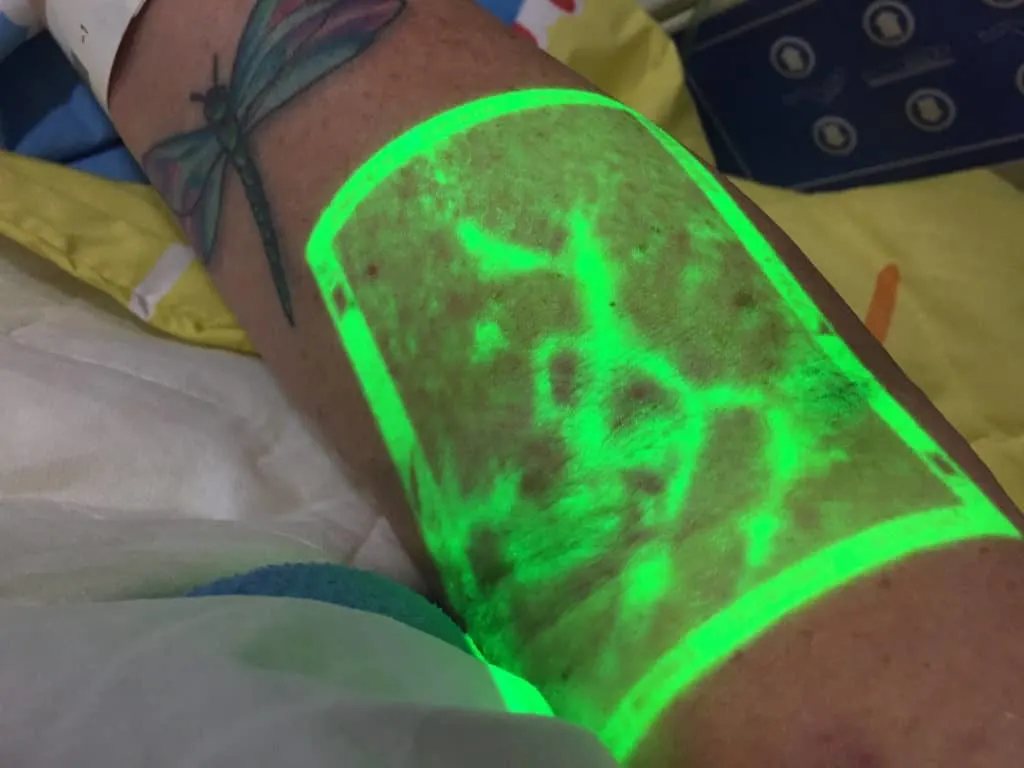

State of the art equipment at Clinica del Caribe included this vein finder gun which projects a below the surface image. No more fails getting blood!

Pete came in, overjoyed after completing administrative arrangements. One special visitor could be designated to have 24 hour access to the ICU. “Whom should I pick?” we joked.

Quickly, we were visited by several doctors: Doctora Luz Stella Acevedo – the very reassuring cardiologist relative of the relative of Pete’s friend, the ICU night doctor, and cardiologist Dr. Wilmer Barros – a very distinguished looking gentleman in a spotless white coat. The vibe was one of concern, competence, and confidence.

Dr. Barros took my hand and asked in simple English, “I need to know, do you want to go home?” “Do you mean right now to the U.S.?” I responded. “Yes,” he confirmed. “Well, no,” I said, “I think it would kill me to fly.” He said, “I think so, too.” At this point, Pete interjected, “I think we need to make a plan for here.” “Oh, we have a plan,” said Dr. B. “When can we get started?” asked Pete. “Right now,” was the answer.

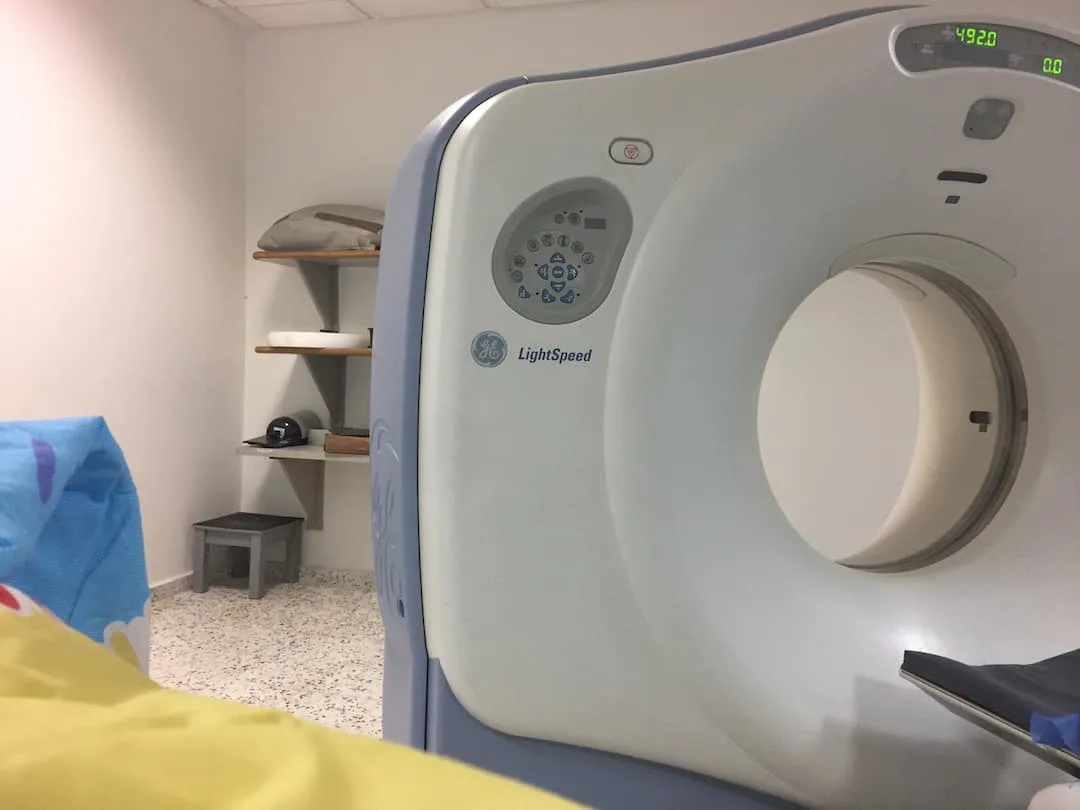

Quickly I was whisked in for multiple scans to determine exactly what was wrong. They revealed an enormous pulmonary embolism in my right lung. Dra. Luz also explained that it appeared my aorta was bulging in a couple of places, but the dissection – which is a separation of layers in the wall of the aorta – had thrombosed. So Lucy’s assessment on the aorta was clarified, and the reason I couldn’t breathe was finally confirmed in accordance with her third hypothesis.

New equipment at Clinica del Caribe

So, I had a good clot and a bad clot. Try asking that in your best Glinda the Good Witch voice: “Are you a good clot or a bad clot?”

What followed: Dr. David Sabbag Abudinen, an engaging young radiologist from Sabbag Radiologos in Barranquilla, who had trained at Baylor and the University of Miami in the United States, broke apart and removed the pulmonary embolism from my lung using a Penumbra device threaded through my system via my groin.

The PE had grown to the size of a baseball cap in the few short days I’d been at the clinic in Santa Marta. This was the reason I couldn’t breathe.

Following the Penumbra procedure, Dr. Sabbag also inserted an inferior vena cava filter in my abdomen, designed to catch any additional clots from moving up into my system. Evidently, my right leg is the clot factory where the PE broke loose and traveled to my lung.

In the meantime, even more sophisticated imaging revealed the dissection in my aorta had clotted together and essentially, healed itself. So, the challenge became managing the need to clot with the need not to. Because the aorta was deemed to be an “older” injury, I needed to return to the USA for medical followup.

I was breathing normally and getting stronger daily. The meals at the clinic were outstanding, and everyone who worked there took joyful pride in their responsibilities. The ICU was peaceful and quiet. The nurses were angels who mothered me. From the vantage point of what I called my little “casita” I observed an outstanding level of holistic professionalism throughout the clinic.

Delicious meals at Clinica del Caribe. That’s fresh squeezed strawberry juice on the right.

When I was transferred out into a private, ensuite room there was a comfortable fold-out bed for Pete and luxurious hotel room details. My brother and daughter, Robin, arrived from the USA to lend moral support and were very impressed.

On the mend at Clinica del Caribe

We left Colombia several days later under medical escort and returned to Minnesota to stay with our kids and begin a different sort of healthcare journey with the Mayo Clinic. In a sense, it was a blessing to have had the PE, as my aorta problems – which are serious – would have likely remained undetected.

Our Prior Experience with Medical Insurance for Traveling Abroad

During our years of international travel, we were never without overseas health insurance coverage. While this was the first major medical emergency abroad we experienced, we did have occasion to file claims with the travel insurance company we’d previously used. One of these was for dental work and another for a trip interruption fail.

We weren’t particularly satisfied with the claims resolution process with the previous company. They employed a third party claims adjuster whose representatives appeared to be more interested in dragging things out to the point where we might abandon due to fatigue. One of the claims was finally settled after I went to Twitter and outed them.

My medical escort and me upon arrival at our daughter’s home in Minnesota

The best medical insurance for travel abroad will give you an opportunity to purchase coverage for a variety of events and circumstances associated with the medical event. Depending on the travel insurance company, these will range from treatment coverage and repatriation to reimbursement for incidental expenses.

Read the fine print, though, as your coverage doesn’t necessarily correlate to your travel health insurance cost. Overseas health insurance coverage can vary. Your carrier’s protocol may be along the lines of “present the bills you paid for reimbursement” or, as in our case with Allianz Insurance, they may prefer to communicate with the provider directly, leaving you out of the process.

Quite honestly, we were happy to be out of the loop. When you are fighting for your life, the last thing you want to do is be drawn into an administrative scenario. Although my hospital bed conversation with our carrier brought immediate results, I would have preferred not to have been involved. This was more the issue on the clinic’s side of things.

Our Overseas Health Scare Became More Complex When Additional Medical Issues Were Discovered

Our medical emergency in South America took a more complicated turn when the imaging revealed serious issues with my aorta. Suddenly, the “simple” matter of a breathing problem had a companion condition that eventually overlapped the travel-insurance related treatment plan.

This meant that our health scare abroad was no longer straightforward. Not only was I in an unacceptable situation at the first clinic, but once our overseas health scare was sufficiently resolved I needed follow-up care for the secondary condition. While this secondary condition wasn’t their responsibility, our coverage provided for our repatriation on the basis of the first condition. This allowed for a seamless transition into the Mayo Clinic system once we arrived in the USA. Allianz took care of all those details, which would have been burdensome to arrange.

What the Best Medical Insurance for Travel Abroad Does For You When You’re in the Midst of an Overseas Health Scare

The best medical insurance for travel abroad will have the travel insurance company step in on your behalf and leave you to the business of being cared for and recovery. But, because complications can occur quickly in the midst of an overseas health scare, you’ll want to assess how nimble your travel insurance company will be. The priorities should be getting you the care you need where you are, and then getting you to where you can continue with care if need be.

In our case, Allianz assisted in getting me from an unacceptable situation to where I could receive first class treatment in Colombia. When I was sufficiently stable, they then arranged for me to return to the United States with an escort who was an EMT.

This was enormously reassuring in light of the serious nature of my condition. We were very fearful that changes in air pressure might cause fluctuations in my blood pressure which would put the aorta under strain. Having a professional to navigate the nitty-gritty details in the airports and expedite our processing was very much appreciated.

When you’re evaluating medical insurance for traveling abroad, you’ll want to assess your personal risk tolerance and match it up with the offerings from the travel insurance company. This wasn’t our first policy with Allianz Travel Insurance; our first had been top of the line coverage. When I renewed, I think I may have clicked the wrong box online, I’m not really sure. In any event, we had mid-range coverage, which was still quite comprehensive.

How Our Medical Emergency Abroad Resulted in Additional Losses That Could Have Led to More Financial Hardship

You might recall that we planned to return to Panama after our month in Colombia. With our health scare abroad terminating with repatriation back to the USA, we had to figure out what to do with luggage we’d left in Panama awaiting our return.

As it turns out, shipping our large suitcases back to the USA from Panama was going to cost about $1000; there were items in there that needed insurance. We asked the shipper to go through our bags and retrieve jewelry and a few other important items for shipping. The rest of the luggage, mostly clothing, was donated to charity.

Our travel insurance cost might have covered reimbursement of this loss had I selected the higher level of coverage. As it was, we arrived in snowy Minnesota in flip flops and tropical attire. Likewise, Pete incurred hotel expenses in Santa Marta, and we had a couple of hotel days in Barranquilla awaiting the travel insurance company medical escort’s arrival.

A travel-insurance rate structure will often cover these types of expenses on top of medical expenses, so if your budget might take a hit paying for these yourself, you will want to consider adding coverage.

Conclusion: Short Term Medical Insurance for Travel Abroad is Imperative

By now, if you’ve read this far, we hope you’ve concluded that overseas health insurance is a must whether you’re going on vacation or planning on lengthier travel. A health scare overseas is no picnic under the best of circumstances.

This overseas health scare was more drama than we’d ever care to repeat, but we’re hopeful that telling our story will cause you to evaluate your existing coverage and be prepared. And please, please don’t ever go without coverage. The cost of travel insurance is so minuscule compared with what could happen. Make room for it in your budget and don’t let it lapse. If you travel frequently, you may want to consider purchasing an annual travel protection plan.

Once You’ve Bought a Travel-Insurance Policy, Do These Things Before Your Trip

Photo Credit Pixabay

Now that we’ve covered travel-insurance related issues with this story, we’ve got a few more items for you to consider before your next trip:

1. Remember when the first clinic we went to wasn’t taking new patients? We wound up in a Cuckoo’s Nest clinic. And remember how we needed to get to a quality clinic that was three hours away from the first one? Know where quality health care providers and hospitals are in relationship to where you’ll be. Assess the cost of getting yourself to quality medical care from remote areas.

2. Never underestimate the power of connections. We wouldn’t have known about Clinica del Caribe had Pete’s friend from kindergarten not intervened and asked his relative in Bogota for help. Even though Bogota was across the entire country from where we were, it was a story of relatives of friends, relatives of relatives, and friends of friends, all playing a part in saving my life. This is a debt we can never repay, except to possibly step up when we are called for help in some other situation.

3. Inquire about cultural differences and expectations. Are patients expected to provide their own bedclothes, nightwear, food, or anything else as was expected of us in Santa Marta? It would have been nice to know that. Pete thought it was so convenient there was a store selling pillows in the neighborhood of the clinic, but turns out there was a reason it was located there. In Colombia, unless you pay for ambulance insurance, it’s on you to get yourself to the hospital or clinic.

Photo Credit Pixabay

3. If there’s a language barrier, decide how you are going to communicate. Google Translate on our phones was a lifesaver. My high school Spanish was invaluable, but limited in terms of medical terminology. Will you be able to make yourself understood, and, in return, understand what you’re being told? Many Americans mistakenly believe English is widely spoken throughout the world. While that may be the case in metropolitan areas, the reality is you can’t expect that English speakers will be at your beck and call in countries where it is not the official language.

4. How will you communicate with your service providers in the USA? We bought data plan only SIMs in Colombia for our iPhones. We could have used some talk time in order to call the insurance company instead of having to use Google Voice and a limited clinic wifi connection at the first clinic. While we would have preferred to maintain all communications with emails in order to leave a virtual paper trail, travel insurance company protocol favored the telephone. Until companies change this, you’re the one who will have to adapt.

5. Don’t be unaware of the quality of health care available in other countries. Clinica del Caribe in Barranquilla delivered superlative, Mayo Clinic-quality care with state of the art equipment. Check the World Health Organization rankings for countries in which you’ll be to get an idea of how they compare, and don’t be shocked when you realize where the USA is by comparison.

6. Many Americans who travel abroad think it’s appropriate to “pull rank” and make unreasonable demands. It’s hard to walk the thin line between the assertive and the obnoxious, particularly when cultural differences move the goalposts from what we’re used to. Don’t demand the impossible, and curb your temperament. Be cognizant of who can effectively advocate for you and acknowledge people who are doing good work, but be prepared to “go Turkish” when necessary with others.

This has turned into a doozy of a post. As I write this, we are still grappling with the previously undiscovered issue with my aorta and our travel lifestyle is in suspension. Adjusting to this change has been challenging, but the silver lining is we get to spend time with our daughter and son-in-law while I’m being treated at the Mayo Clinic here in Minnesota. Our insurance carrier followed up with payments directly to Clinica del Caribe on our behalf, and reimbursed us for the majority of the expenses we submitted in accordance with our coverage.

We will forever be grateful for the love and care we received from so many people in Colombia. It is no small thing to be on the brink of death and realize your fate is out of your hands. Colombia gave me back my life.

When we do get clearance to travel internationally again, the first order of business for any trip plan will be to purchase medical insurance for travel abroad from Allianz. We can’t recommend them highly enough. It’s our hope that the story of our medical emergency will influence your travel decision-making as well. Wishing you the best of health and many happy travels in the years to come.

Pinnable Image:

Tips for Trip Success

Book Your Flight

Find an inexpensive flight by using Kayak, a favorite of ours because it regularly returns less expensive flight options from a variety of airlines.

Book Your Hotel or Special Accommodation

We are big fans of Booking.com. We like their review system and photos. If we want to see more reviews and additional booking options, we go to Expedia.

You Need Travel Insurance!

Good travel insurance means having total peace of mind. Travel insurance protects you when your medical insurance often will not and better than what you get from your credit card. It will provide comprehensive coverage should you need medical treatment or return to the United States, compensation for trip interruption, baggage loss, and other situations.Find the Perfect Insurance Plan for Your Trip

PassingThru is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

To view PassingThru’s privacy policy, click here.

Vincent

Tuesday 17th of October 2023

Hi I’m curious if your travel insurance terminated your policy upon medical return to your country? I’ve heard that is standard practice I’m assuming because of how expensive it is. So I wanted to hear about your experience with the insurance company after your return regarding that

Betsy Wuebker

Wednesday 18th of October 2023

Hi Vincent, The policy we had was temporary in nature, covering the specific trip. So it was designed to sunset, and we picked up traditional insurance coverage once we were back in the U.S.

Steve

Sunday 20th of December 2020

This was quite a post (I discovered it while reading about the Reunification Express).

I've used travel insurance from Allianz, but your post encourages me to think of some features that I may need.

Nice pic of the ambulance from Baltimore City station #55!

Suzanne Fluhr

Saturday 5th of January 2019

Somehow, I missed reading this when it was first published. Even though I followed along in almost real time as your not fun vacation unfolded, this narrative is still a very evocative read. As a fellow baby boomer, I've completely absorbed the fact that it's often not what you know, but who you know and then, in some cases, who they know or even who they know who knows yet someone else. It's kind of remarkable that your chain of "knows" started with Pete's Minnesota friend from kindergarten, and ended up with the governor of a Colombian province. In any case, I'm glad you've decided to make Philadelphia your first test trip. I hope you don't need them, but as you know, we have some Philly medical connections. ;-) Hasta pronto!

Betsy Wuebker

Saturday 5th of January 2019

Hi Suzanne - Yes, I'm convinced it was divine intervention. There is no other explanation. Looking forward to seeing you in Philly!

Susan Greet

Saturday 9th of June 2018

Betsy reading first hand your medical nightmare confirmed what we have known all along. Having good travel insurance is essential for everyone wanting to travel abroad. You clearly are a very strong woman to have held it together under unimaginable circumstances. I'm thankful you are receiving the care you need and wishing you a speedy recovery. I hope others read about your experience and take it to heart.

Betsy Wuebker

Sunday 10th of June 2018

Hi Susan - Yes, it's inexplicable that someone would forego travel insurance. This is just waving a red flag in front of the bull. Thanks.

Anita @ No Particular Place to Go

Thursday 7th of June 2018

Even though I knew your story had a positive outcome Betsy, I found myself on the edge of my seat reading through your graphic description of your recent medical crisis. What a nightmare. I think your point of a traveler's need to educate themselves on what medical care is available at each destination is so important as is a patient's need for a trusted friend or relative to be an advocate for them and make sure that they're receiving the necessary care. The "What if" scenarios that might have happened if you hadn't had people intervene on your behalf as well as good travel insurance are sobering. Wishing you a speedy and smooth recovery, Betsy and sending along my greetings to Pete, too. Hopefully, many of your readers will find your story enlightening and make preparations for a just-in-case scenario.

Betsy Wuebker

Thursday 7th of June 2018

Hi Anita - Yes, and you and Richard have had your share of medical stories abroad to tell as well, haven't you? It was very difficult to get back in the emotional head space to write this story, but I hope readers will understand that good trip preparation includes a few clicks to buy good travel insurance. Still working on getting to a place where we resume our travel lifestyle and hope to meet up with you again in your part of the world. :)