A chance encounter on the last leg of Vietnam’s Reunification Express train from Hanoi to Saigon leads to forgiveness and acceptance of shared history.

Note: We have previously written about our memorable trip on the Reunification Express in Hanoi to Ho Chi Minh City by Train, which is a factual account with information on how you might replicate our experience in Vietnam. What we haven’t shared publicly until now is a life-changing encounter which occurred on the final leg of that journey. This is the story.

This article contains affiliate links and/or references to our advertisers. We may receive compensation when you click on or make a purchase using these links.

As the train chugged toward the crowded platform, we quickly went into autopilot: find the right carriage, hoist luggage aboard, scope out the shelving under the ceiling – was it sturdy and spacious enough? Smile back at curious fellow passengers, look for a gallant savior who might give our bags a swing overhead or help drag them into an alcove.

This was the fourth leg of our journey on Vietnam’s Reunification Express, and Carriage #2’s Seats 21 and 22 were to be our bivouac for seven hours. Familiarizing ourselves with the personal space around our seats, we prioritized and stashed individual items. All around us, other passengers were doing the same.

Discover the 10 best hotels in Hanoi.

Judging from its washed out interior and dilapidated state, I estimated this carriage had been around since the restoration in 1975. The Reunification Express runs along the coastal spine of Vietnam from north of Hanoi to Ho Chi Minh City. When the former Saigon fell and what is referred to here as the American War was over, the entire length of the route was reopened for the first time in decades, hence its name.

Heavily targeted by both American and North Vietnamese bombs, the line underwent subsequent repairs at over 150 stations and more than 1300 switches in southern Vietnam alone. Forty years later, we were on it heading south from Hanoi, breaking up the trip in manageable increments for sightseeing and overnight stays.

This leg between Nha Trang and Ho Chi Minh City had cost us an extra half-cent per kilometer for an assigned “soft seat.” It seemed like a real bargain rather than suffering on crowded wooden benches the Vietnam Railways System euphemistically referred to as “hard seats.” Even so, Seats 21 and 22 sagged, their dingy upholstery dusty and their padding shriveled.

Beside me, limp curtains of faded satin with frayed, fringed tiebacks could be drawn against the sun, or knotted haphazardly off to one side to frame the view. I chose the latter. I do like staring out the windows of a train.

As we settled in, a group of about a dozen men in late middle age glad-handed and back-slapped, passing food and drink amongst each other in the rows directly ahead. “Uh-oh,” I thought. Salesmen, most likely. Headed for some kind of convention or meeting in the city. Going to kick up their heels on this long December weekend, no doubt, no wives allowed.

One who was clearly in a position of authority – a manager, I surmised, the boss man – moved between their pairs and groups of three. By joking and calling back and forth, he drew them all into boisterous hijinks, playfully cuffing an ear or punching an arm. This was a group who knew each other well, out for a good time.

Weary at the thought of what might yet transpire as they got a little more into their cups – was that tea or something stronger in their thermos? – I closed my eyes just in time for the seat back in front of Pete to crash into his lap. “Whoa!” we both blurted simultaneously.

A sales guy turned around apologetically, smiled, shrugged and motioned. Broken mechanism. No reclining for him. Back up he bent into a 90-degree angle. Secretly, I was rather glad. We’d staked out our territory with the hope of no encroachment into our little bubble of space. Eyes remained on us, the only foreigners in the car.

The Reunification Express pulled out and climbed, picking up speed high above the coastline to cut through the mountains south of Nha Trang. Over the noise from the track came the clicks of the conductor’s ticket punch, then the rattle of the rickety hot food cart. Upon it, an oversized red plastic bucket of steaming white rice was balanced. You received a heaping scoop in a plastic bowl. You could then choose to have pungent, yet indeterminate, pieces of meat or fish with bones swimming in a thick brown sauce ladled over your rice from a dripping dipper.

A snack cart would follow, its main attraction a row of flat seedy discs swinging by their cellophane wrappers. These looked like something you might hang on a tree for the birds: spiced sesame rice crackers. Certain kinds were tasty, others definitely not. In the alternative, you could choose a cylinder of Pringles (flash of recognition!) or boiled peanuts. To drink there was canned soda, sweet Vietnamese coffee or scalding green tea served in a china cup and saucer.

We contented ourselves with what we’d brought aboard. The salesmen shared their food with each other and distributed paper cups filled from the thermos as their horseplay subsided. To the sounds of munching and the crackle of cellophane, Carriage #2 lurched and swayed, hurtling steadily along, with many of our fellow passengers, lulled and sated, nodding off to sleep.

As I stared out the window with chin in hand, we emerged from the mountains and descended. Looking through my reflection in the glass at the countryside beyond, I remembered writer Paul Theroux. After riding this line some years before, he’d mused, “Anything is possible on a train: a great meal, a binge, a visit from card players, an intrigue, a good night’s sleep, and strangers’ monologues framed like Russian short stories.” True.

Invariably, I would observe not only the landscape but my fellow travelers, too, and this always took me inward. And then, generally, clarity would ensue. There was a lot of possibility on a train, yes, I agreed.

Scenery moved past my gaze in a silent film reel of images. Flooded paddies dotted in the old way by family graves above the ground spliced into elevated dirt lanes with simple arched bridges of stone or wood. These led to villages of narrow shop houses, their mildewed colors and French details rising above muddy streets.

There were wet square plots defined by low earthen walls teeming with ducks, geese or fish being raised for market. A solitary figure in a conical hat punctuated greening fields or pedaled a bicycle cart. Pastoral. Orderly. Peaceful. Timeless.

“You! Where are you from?” the voice startled and finger pointed. It was the salesmen’s ringleader who had crossed the aisle to stand in front of Pete. We’d been asked this often in Vietnam.

Invariably the questioner’s eyes would widen with our answer and then we’d get, “America! Welcome! Thankyouverymuch!” This was usually the extent of their English in the secondary cities, and so delighted were they to speak it that you couldn’t help but be delighted back.

A man in Quy Nhon had made a u-turn on his bicycle just to look us over at a sidewalk table. “Americans!” he had beamed, riding off with a joyous look that said, “Holy cow, I can’t believe it!”

A tiny grandmother had clasped both my hands in hers at a curb in Nha Trang as I hesitated. After guiding me across four insane lanes of traffic, “America!” she stated emphatically, then drew herself up proudly to just below my shoulder for a photo.

And this time was little different: the obligatory exchange ensued, the cellphones came out to show photos of his grandchildren, our home in Hawaii. “Hawaii?” he was gleeful, as if that didn’t beat all. “Aloha!” Yes, aloha! “You go Saigon?” Yes, we go Saigon.

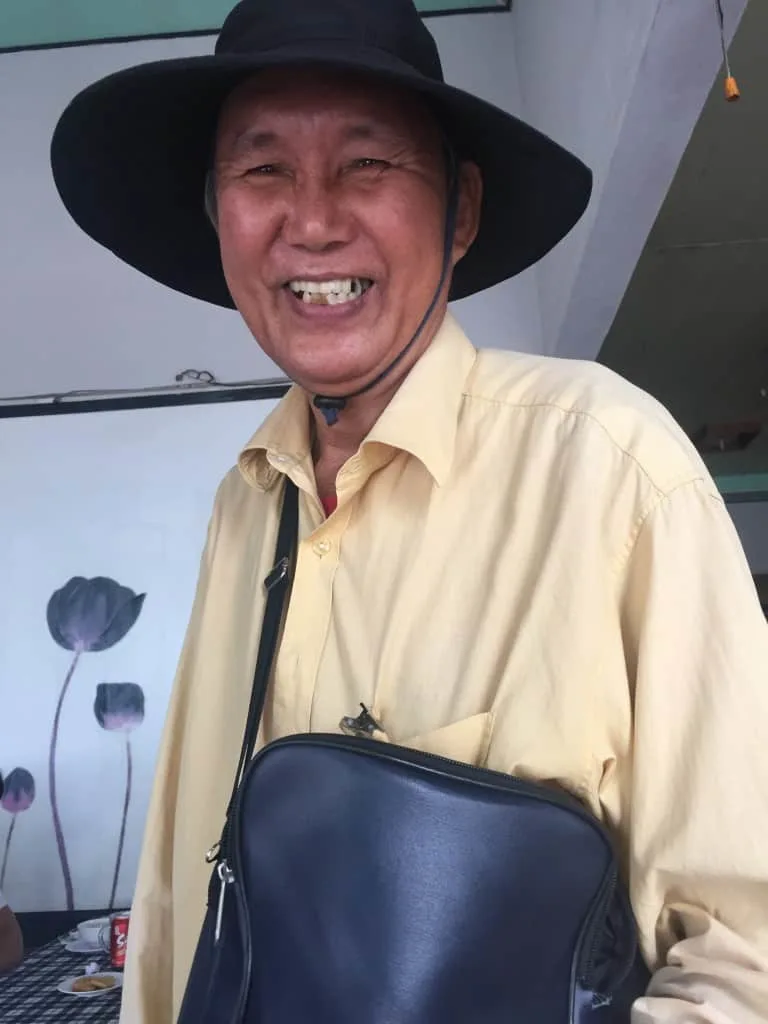

“Me,” pointing at himself, “Bien. I live Hanoi. You like Hanoi?” Yes, we like Hanoi very much, very beautiful. “Where do you go in Vietnam?” Hue, Quy Nhon, Nha Trang. “You?” pointing again to both of us. Peter. Betsy. “Ahh. How old are you? I am 64!” Proudly, with a sweet, self-conscious, toothy smile.

“You go Saigon. Me my friends,” gestured Bien toward his cohorts, “go Saigon now. Last time we go Saigon from Hanoi. Nineteen seven five, three months walking.” At this I froze, hoping my face maintained a pleasant mask. In 1975, Hanoi to Saigon on foot for a male of a certain age likely meant this guy and his pals had been North Vietnamese Army.

I have an uncle who was assigned to the Medevac hospital in Long Binh in those days. On the night of his 80th birthday a few years prior to this trip, we had first heard him tell of being strafed by automatic gunfire as he showered off bloody surgical remains.

The alarm had sounded that three sides of their perimeter had been breached, but they kept working. “Our finest hour,” he remembered. “We performed in the way we were trained to do. I was never so proud of a team.” It was the Tet Offensive.

In college, I knew someone who starved himself down to emaciation, another who ate tinfoil so it might show up weird in an x-ray, and still another who practiced acting crazy ahead of the final draft lottery. The two whose numbers had them go as far as the medical exam were sent away with deferments. The third hadn’t been even remotely close to being called.

At least one acquaintance headed to Canada as a conscientious objector. The spring of my graduation was marred by images of the last American helicopters in Saigon, careening drunkenly away from the embassy roof, overladen with desperate, screaming people hanging from their skids.

After school in Detroit for a while, I’d had a boyfriend who’d done two tours. He wasn’t quite right in the head, and I broke it off after he brought out Polaroids of severed ears and dead Viet Cong. Two decades later, another beau couldn’t sit through Saving Private Ryan, traumatized still. He confessed to hiding alone in a hole at night, listening to footsteps and enemy conversation, suppressing silent sobs, daring not to breathe.

Now I was sitting on a train called the Reunification Express in a soft seat somewhere in South Vietnam while these thoughts converged, dancing around the obvious. Any one of these guys in Carriage #2 could have encountered someone I might have known at the opposite end of a gun barrel back then.

Warily, I assessed our acquaintance’s careful expression. Surely, he was thinking the same thing.

“59!” exclaimed Pete with a jovial grin, either not realizing or in spite of it all, pointing to his own chest, firmly jolting us back into the present. “61,” I said quietly, and watched our new friend’s face relax. Neither of us was old enough to have been a direct adversary, so there was that.

“My friends,” Bien said, softer now and more gently, waving his hand toward his group again. “We Army, go to Saigon. Gathering.” In our faces there must have been a question. “All our friends, we go for Army friends who died. Bring flowers to honor.”

Speaking directly to me, his eyes filled with tears. So did mine in response. We looked away from each other. There it was: the simple instant proving anything could happen on a train.

Clearing his throat, Bien looked at Pete, “I was teacher. Thirty years. What is your work?” While Pete attempted to explain, I sat silent. These weren’t traveling salesmen at all. This was a squad reunion.

This time the mission was to participate in the equivalent of a Memorial Day ceremony on the 40th birthday of the postwar Vietnamese Armed Forces.

My uncle had gone back to Texas to pick up the pieces. While they were stitching our boys together in Long Binh, his family at home had fallen apart. He shipped out again to Germany for a stretch, and then retired a Colonel. Now he gives walking tours of the beautiful gardens surrounding his home in the Midwest.

My college friends went on to graduate and set off on a conventional path to work corporate jobs, as I had. I’d lost touch with the two boyfriends who still carried their demons decades apart, and last I heard no one really knew what had become of the hometown conscientious objector.

All that had ever been done with all that had happened back then was to take it out from time to time and look it over, seeking answers which would never appear.

“We are happy you come to Vietnam,” said Bien. “Please, welcome.” Smiling, he returned to his seat after I snapped a photo of him and Pete together, arm in arm.

I thought of the Buddha, who, when asked about forgiveness, replied that men are like rivers changing from moment to moment: “The river has flowed much since yesterday and though I may look the same, I am not.”

The train slowed as we entered the outskirts of Ho Chi Minh City. Bien and his group stood and leaned toward the windows, looking out, obviously seeking a landmark from old Saigon they might recognize, pointing in this direction and that. The conversation ebbed and subsided.

I watched how each man’s expression changed or his eyes turned far away as the memories appeared. It made me think of fast clouds casting rapid shadows across tracts of land and then disappearing on the horizon. He would leave the past where it was and return. The river had flowed; he was not the same. It was stunningly beautiful.

Pulling into the station, all of us performed our individual boarding rituals in reverse. From Seats 21 and 22, Pete went one way after a large suitcase and I another, to exit from opposite doors. As I stood on the platform waiting, the many passengers on the Reunification Express spilled out of all the carriages and streamed toward the exit.

From Carriage #2 the Army buddies emerged one by one, their clothing betraying whom they had become: a mechanic’s gray jumpsuit with red-stitched name on the pocket, a countryman’s cap, a white button down shirt. Each met my eyes with a wave or a nod.

Last came Bien, in a scuffed butterscotch leather jacket, carrying a simple canvas duffel, walking over with his hand extended. “I wish you very good life,” he smiled. “The same to you,” I answered. He turned and was swept away in the crowd.

Discover the 10 best hotels in Ho Chi Minh City.

Pinnable Image:

Tips for Trip Success

Book Your Flight

Find an inexpensive flight by using Kayak, a favorite of ours because it regularly returns less expensive flight options from a variety of airlines.

Book Your Hotel or Special Accommodation

We are big fans of Booking.com. We like their review system and photos. If we want to see more reviews and additional booking options, we go to Expedia.

You Need Travel Insurance!

Good travel insurance means having total peace of mind. Travel insurance protects you when your medical insurance often will not and better than what you get from your credit card. It will provide comprehensive coverage should you need medical treatment or return to the United States, compensation for trip interruption, baggage loss, and other situations.Find the Perfect Insurance Plan for Your Trip

PassingThru is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

To view PassingThru’s privacy policy, click here.

Jenny

Sunday 26th of June 2016

Betsy this is a beautiful piece of writing, and what an incredible encounter to have had. It's too easy to go to Vietnam, visit the museums and learn all about the war, but it's only theory. But people who lived through that time are still all around, and while they have mostly forgiven, it was a horrifying and dramatic time in their lives (I feel like those words really don't adequately express how it must have been....) and they certainly haven't forgotten. Meeting these people makes it all so much more real, and definitely touches your heart in a way that no museum exhibit ever could.

Betsy Wuebker

Sunday 26th of June 2016

Hi Jenny - You're so right that experiences like these can bring things full circle. Thank you.

Sue Reddel

Sunday 26th of June 2016

Thank you so much for sharing this moving and personal post. Your Buddha quote "The river has flowed much since yesterday and though I may look the same, I am not" really says it all. I continue to admire your work & travels.

Betsy Wuebker

Sunday 26th of June 2016

Hi Sue - Yes, it was as if the quote came to life. Thank you so much.

Nathalie

Sunday 26th of June 2016

What a great story, nice to see people who are able to put those horrible events behind them but still able to remember and honor the people who were there.

Betsy Wuebker

Sunday 26th of June 2016

Hi Nat - Yes, it is amazing. Thanks.

Laura Lee Carter

Thursday 23rd of June 2016

Thanks for sharing this special experience! I lived in Thailand at the end of the Vietnam War, and I couldn't help thinking how the lovely people I met there could have been Vietnamese.

Betsy Wuebker

Friday 24th of June 2016

Hi Laura Lee - We spent a little time in Northern Thailand and Laos and I couldn't help but think the borders in this region are so arbitrarily established, with little to no reference to families, groups and tribes. So yes, a valid consideration.

Judy Freedman

Thursday 23rd of June 2016

What an amazing story. Enjoyed reading all about your trip. Sounds like it was truly a life changing experience.

Betsy Wuebker

Friday 24th of June 2016

Hi Judy - It was indeed. Thanks.